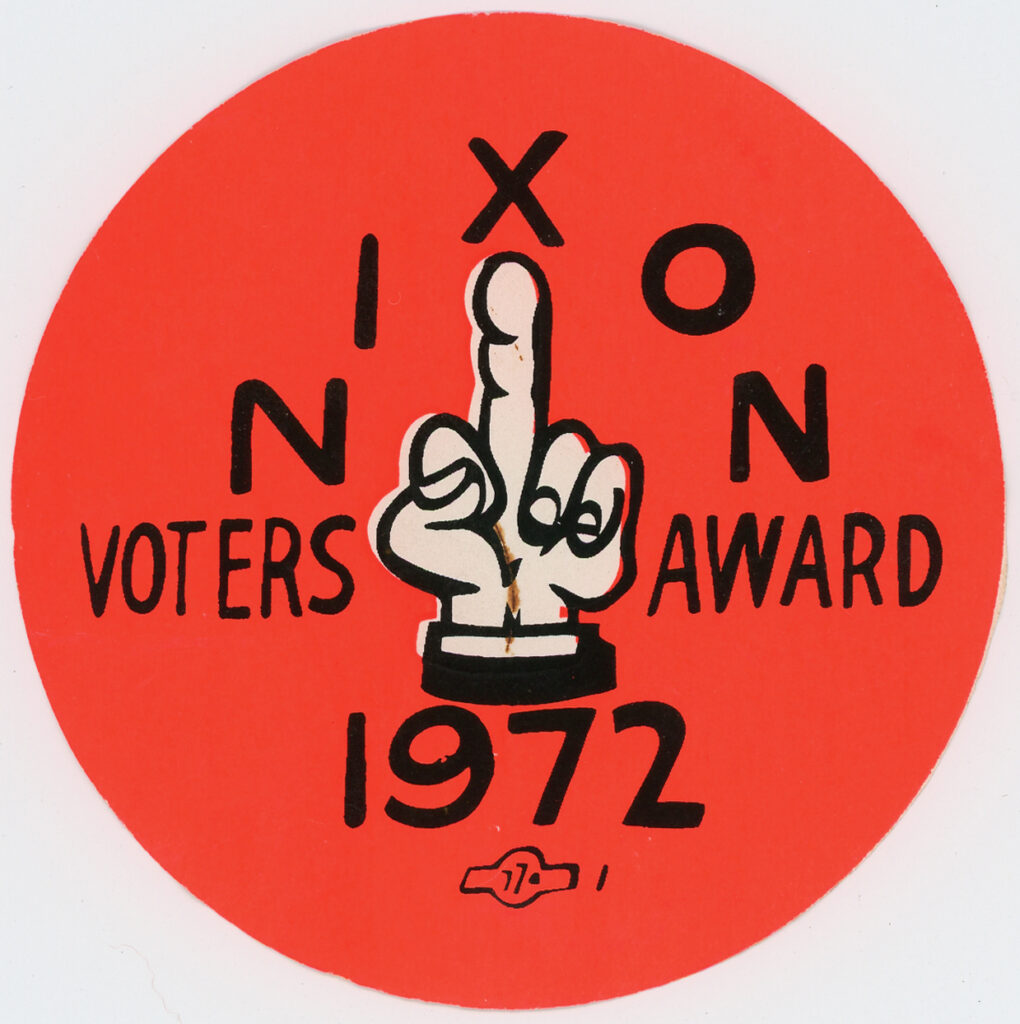

Featured contributor Kevin Howley on Richard Nixon sticker(s)

- Published

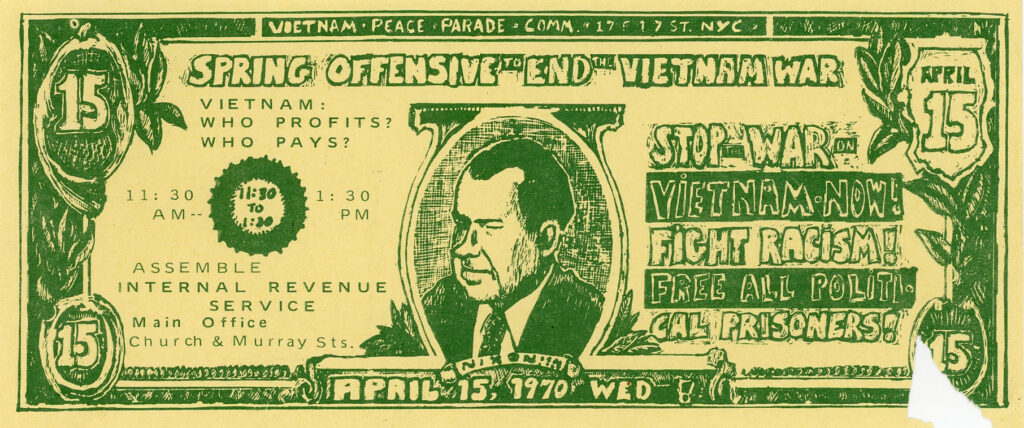

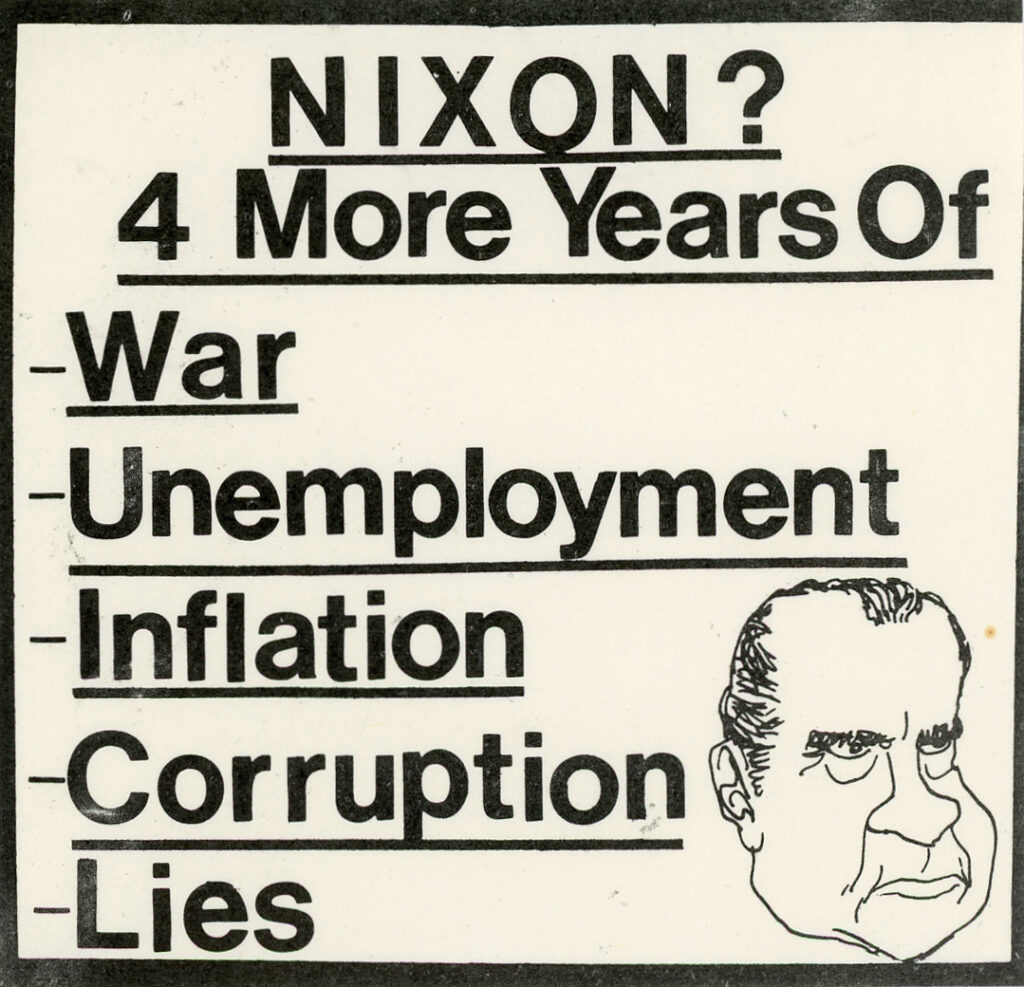

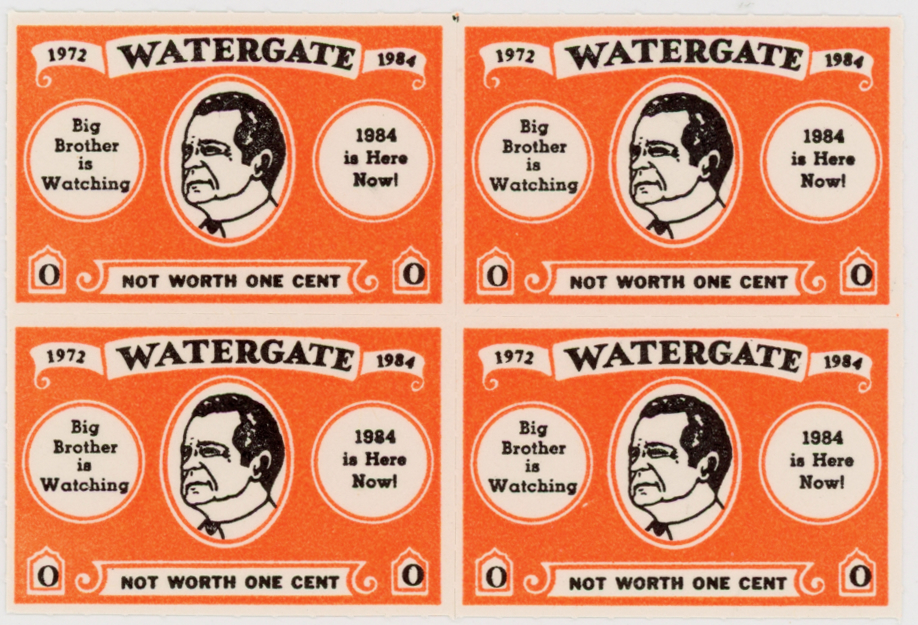

- in "Paper Bullets" exhibition, all

Kevin Howley (PhD Indiana University, 1998) is a writer and educator. His work has appeared in Journalism: Theory, Practice and Criticism, Social Movement Studies, Literature/Film Quarterly and Interactions: Studies in Communication and Culture. His most recent book is Drones: Media Discourse and the Public Imagination.

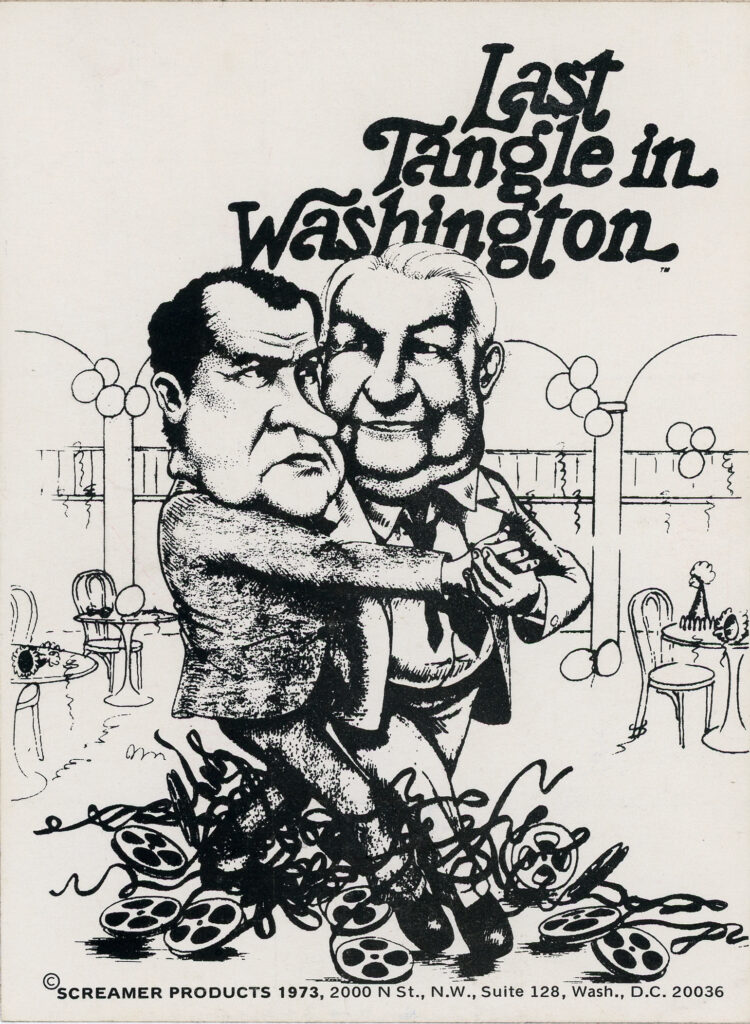

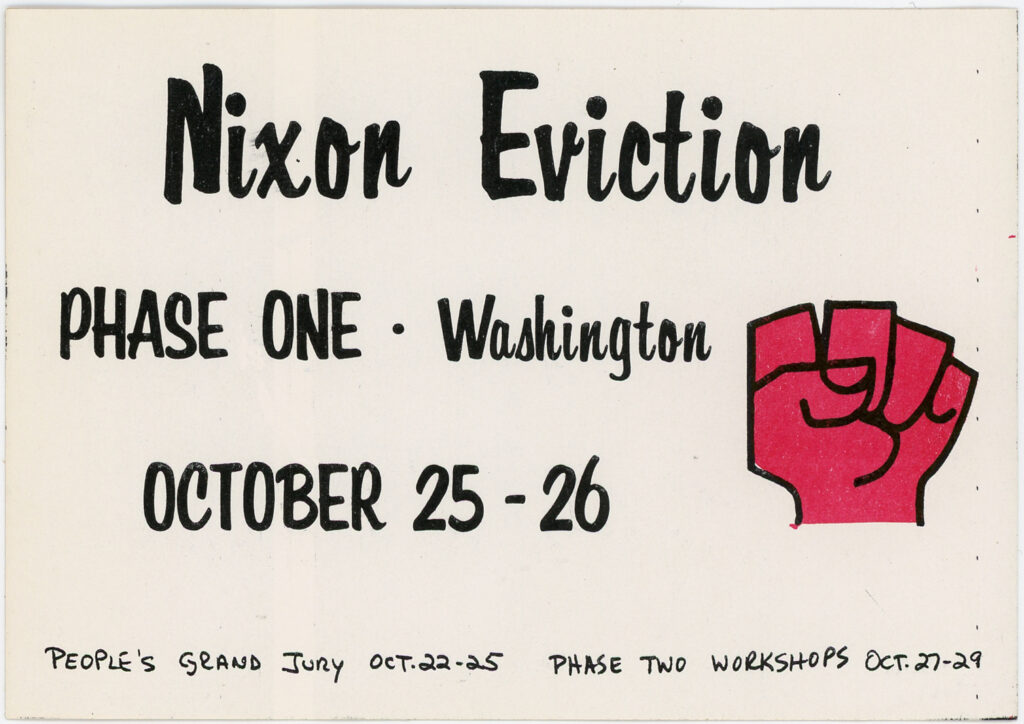

[Editor’s Note: Kevin was one of the first people to contact me offering to contribute to the Paper Bullets exhibition and book. His original plan was to write about the Richard Nixon “Watergate: The Proof Increases Every day” sticker, but after seeing his final essay, I asked if I could include other Nixon stickers, too.]

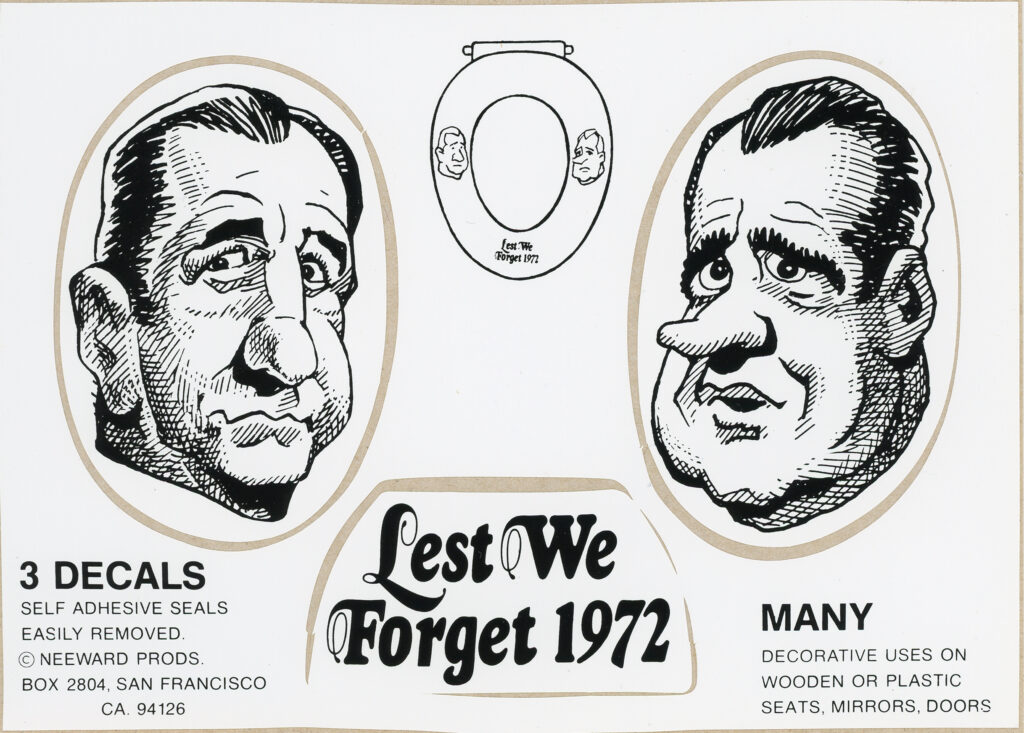

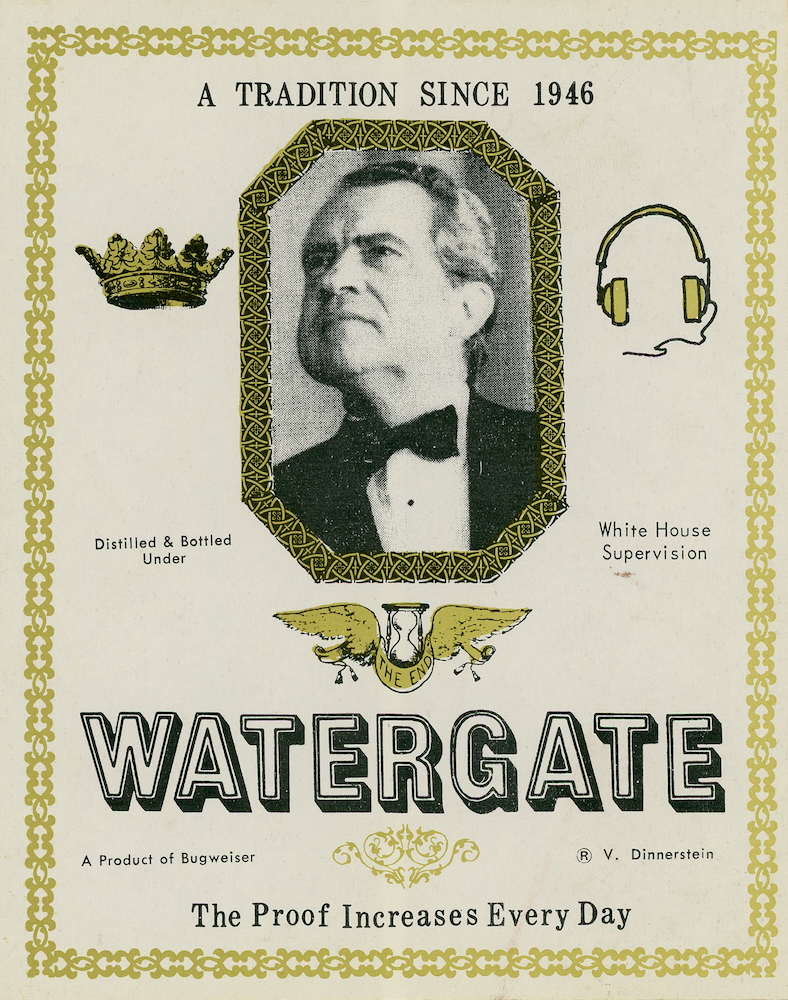

Watergate: The Proof Increases Everyday, V. Dinnerstein, ca. 1973

This essay examines the political sticker “Watergate: The Proof Increases Every Day,” with an eye toward contextualizing growing public distrust of President Richard M. Nixon in the wake of the Watergate scandal, subsequent revelations about the President’s secret Oval Office recording system, and rumors of his drinking problem. The essay proceeds with an account of Nixon’s rise from obscurity to become a leading figure in post-World War II US politics. Following this, I recall Nixon’s tumultuous second term in the White House and the cascading crises that forced him from office on August 9, 1974. Throughout, I underscore the sticker’s sly references to Nixon’s reputation for political dirty tricks, the mounting evidence of his role in the Watergate coverup, and the President’s increasingly erratic behavior in the waning days of his administration. The essay concludes with a few reflections on the historical irony of Nixon’s transgressions in light of Donald J. Trump’s brand of impeachable offenses.

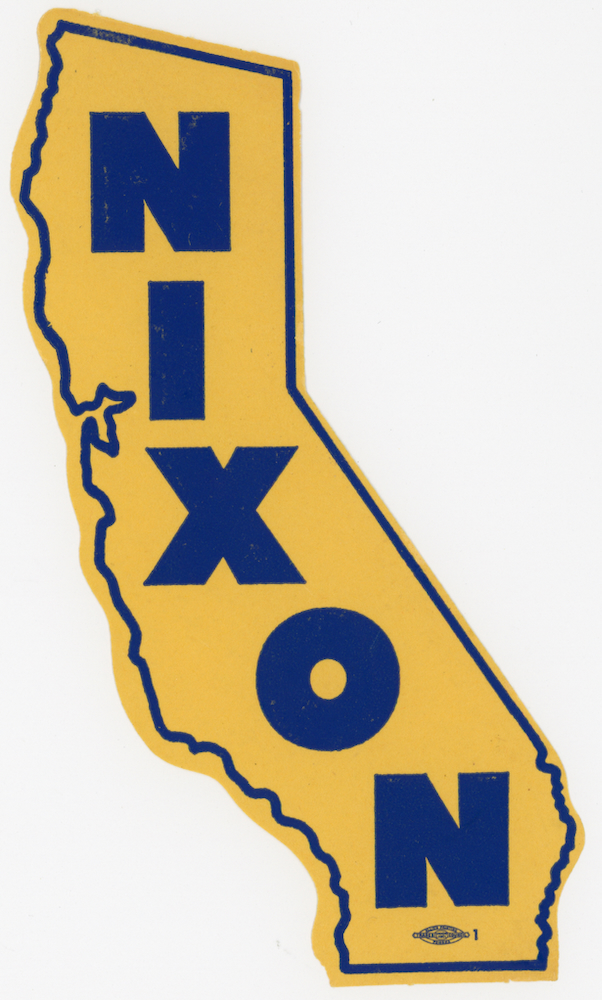

Tricky Dick

In 1946, a group of Republican business leaders in California tapped the relatively unknown Richard Nixon to run against longtime Democratic incumbent, Jerry Voorhis, in the race for California’s 12th Congressional district. Nixon’s campaign manager, Murray Chotiner, who believed early campaigning starts “because you need that time to deflate your opposition,” set about to tarnish Voorhis’ reputation. Despite having authored the Voorhis Act, legislation that required foreign agents to register with the US government, Nixon successfully portrayed his opponent as soft on Communism. Voorhis later recalled, it was “the bitterest campaign I have ever experienced” (Marshall, 1973, p. 16).

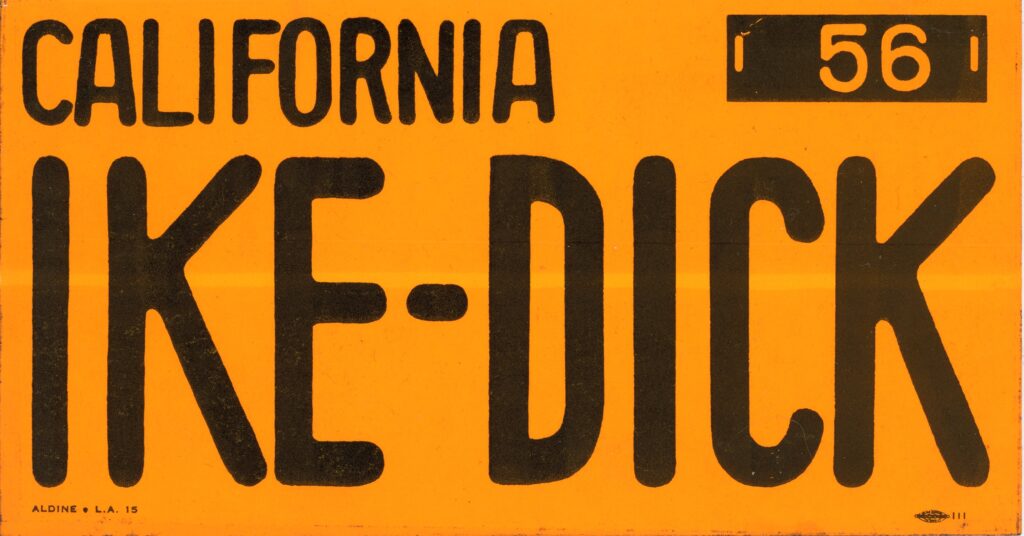

Nixon would use this same approach to win a vacant California Senate seat in 1950 and later used his anti-Communist credentials, most notably his turn as the lead Congressional prosecutor in the Alger Hiss Case, to become Dwight Eisenhower’s 1952 running mate. As historian H. Larry Ingle observes, “Nixon would have remained just another congressman: instead it made him a major political figure and gave him a national reputation as an anti-Communist” (2012, p. 1). While serving two terms as Eisenhower’s vice president, Nixon continued to burnish his anti-Communist bona fides, most memorably in his 1959 “Kitchen Debate” with Soviet Premiere Nikita Khrushchev (Vivian, 2016).

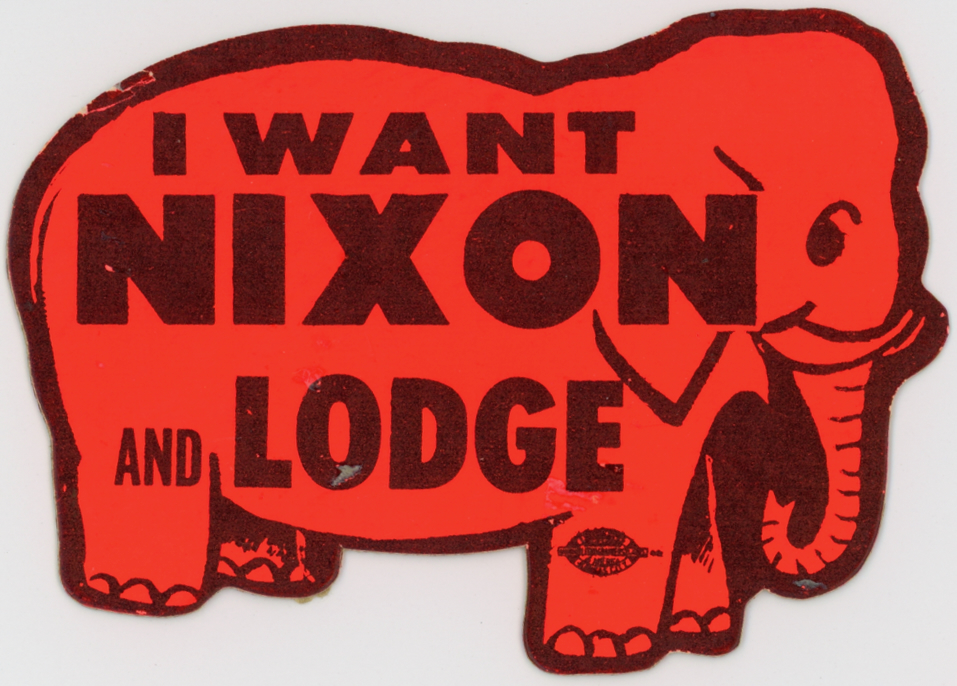

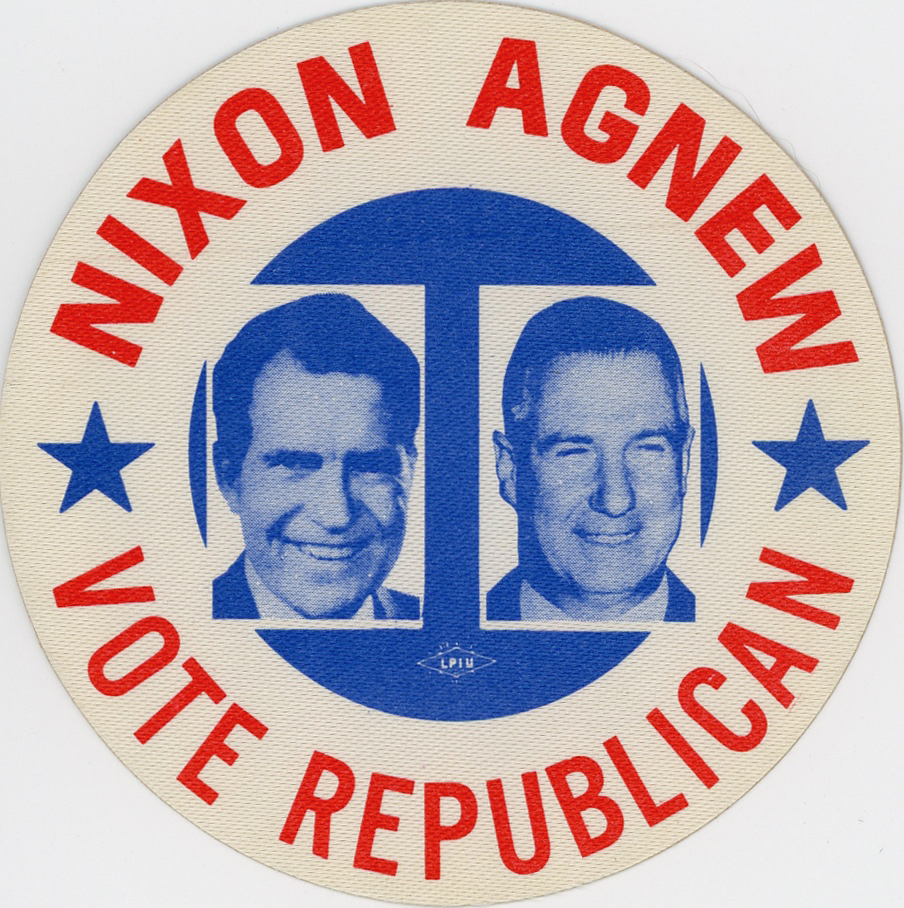

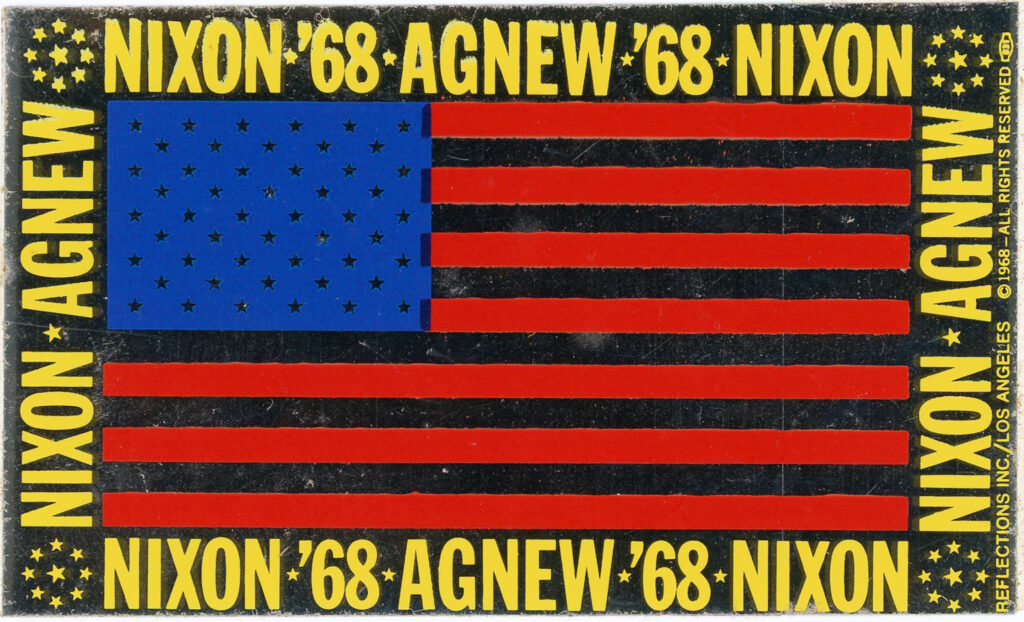

Following a narrow defeat to John F. Kennedy in the 1960 presidential campaign and a failed bid for California governor in 1962, Nixon worked behind the scenes to again secure his party’s nomination for president in 1968. Notwithstanding the campaign’s assertions that this was a “New Nixon” (McGinnis, 1969) the 37th President of the United States never lost his appetite for Machiavellian schemes. Nixon’s reputation for such tactics earned him the nickname “Tricky Dick.”

(Silent) Majority Rule

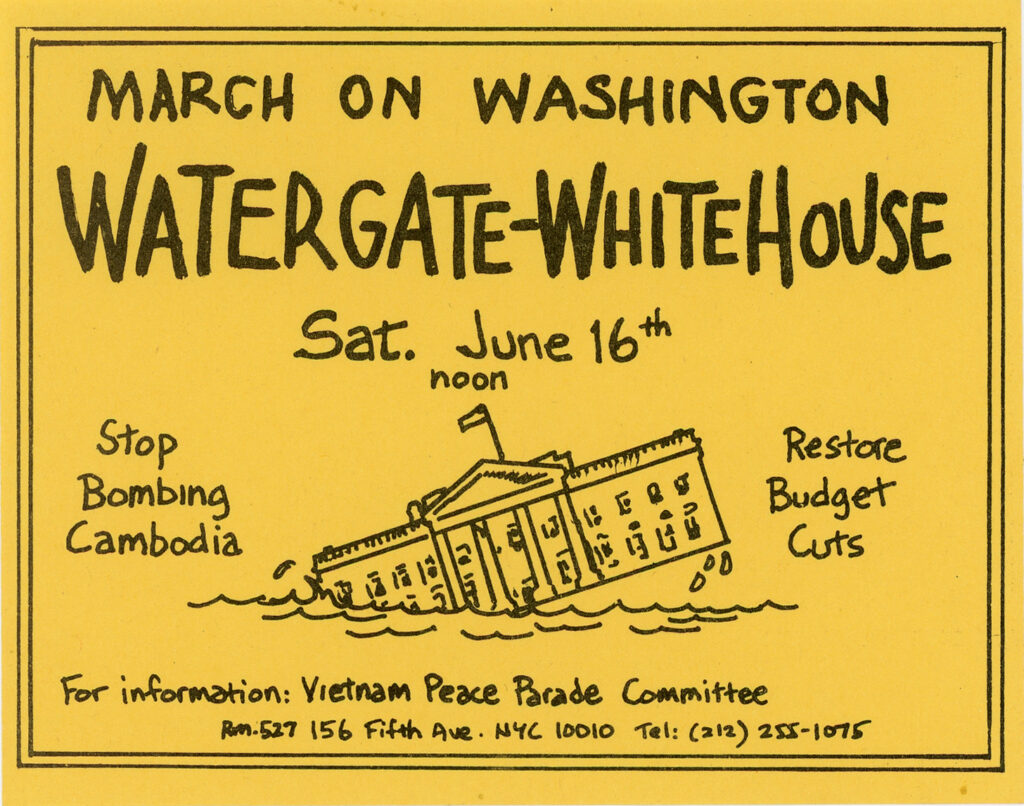

By 1973, the newly re-elected President Nixon was an increasingly polarizing figure. Between his assault on Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society program and the brutal air campaign in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, Nixon became a targeted poster child for the anti-war left. Despite widespread protests, Nixon held firm, backed by the so-called Silent Majority of “law and order” Americans, only to be undone by his own subsequent rampant criminality and presidential imperiousness.

On the eve of his reelection campaign against liberal Democrat George McGovern, Nixon’s “plumbers” broke into the offices of Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist in a failed effort to dig up dirt on the source of a massive leak of classified documents – a secret history of US involvement in Vietnam in what came to be known as the Pentagon Papers. True to form, and seemingly incapable of giving up a grudge, Tricky Dick sought to leverage the papers to discredit Democratic rivals, including former President Johnson and Nixon’s nemesis, even in death, the slain JFK (Thomas & Shackelford, 1997).

Months later, D.C. metro police apprehended the plumbers while they installed surveillance equipment in the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee (DNC), located in the now infamous Watergate Hotel. The story failed to gain much traction during the 1972 campaign, but soon after Nixon’s reelection, the White House’s increasingly desperate efforts to cover up the Watergate break-in began to unravel. Over the course of the investigation, revelations of Nixon’s secret Oval Office recording system set in motion a series of high-stakes confrontations between the President, the Department of Justice, Congressional investigators, and, ultimately, the US Supreme Court.

“Our Drunken Friend”

In The Final Days, investigative journalists Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s harrowing account of Richard Nixon’s last months in office, the president is depicted as drunk and disorderly, spending tortured evenings talking to White House portraits of his predecessors and falling to his knees in prayer as a befuddled Secretary of State Henry Kissinger looked on. It is a dark moment brutally satirized in a 1976 Saturday Night Live sketch featuring Dan Ackroyd and John Belushi as Nixon and Kissinger, respectively (SNL Transcripts).

In a particularly revelatory passage from The Final Days, Nixon’s Chief of Staff, Alexander Haig, refers to his boss as “our drunken friend” (2005, p. 191). Likewise, CBS News recalls an episode that finds Nixon unable to perform during a global crisis. “In October 1973, U.S.-Soviet tensions were peaking over the Arab-Israeli war, and British Prime Minister Edward Heath’s office called the White House just before 8 p.m. to ask to speak with Nixon. ‘Can we tell them no?’ Kissinger asked his assistant, Brent Scowcroft, who had told him of the urgent request. ‘When I talked to the president, he was loaded’” (Report: Nixon Drunk in ’73 Crisis, 2004).

In this context, we can appreciate the sticker’s sly smash up of Nixon’s imperiousness – the crown aside the President’s lofty visage – alongside none-too-subtle references to alcohol: “Bugweiser,” and “Distilled and Bottled Under White House Supervision.” Of course, the headphones to Nixon’s right invoke the secretive Oval Office recording system that would be the President’s undoing. Finally, the phrase “A Tradition Since 1946” atop the sticker and the bottom line of text, “The Proof Increases Every Day” conflate Nixon’s affinity for dirty tricks with familiar tropes associated with wine and spirits.

Coda: From Nixon To Trump

Dinnerstein’s sticker leverages all of this – Nixon’s drinking, his penchant for dirty tricks, the White House tapes – to excellent effect in a Watergate-inspired political provocation, challenging a man who, when confronted with allegations of criminality in the White House, famously told interviewer David Frost, “Well, when the president does it, that means that it is not illegal” (Nixon, 1977).

Today, this imperious attitude sounds eerily familiar. Noting parallels between Nixon and Trump, historian John Farrell assessed Trump a mere three months into his presidency this way, “In just 45 days, we’ve had all the events that happened in the Nixon years … We’ve had the ‘press is the enemy’ line, the firing of an attorney general, massive protests in the streets of Washington, talk about eavesdropping and wiretapping, and a press secretary who gets ridiculed by the media” (Pierleoni, 2017).

In retrospect, “Tricky Dick” Nixon is a third-rate huckster compared to the flagrant abuses of presidential power and authoritarian aspirations of one Donald J. Trump.

References

Ingle, H. L. (2012). Richard Nixon, Whittaker Chambers, Alger Hiss, and Quakerism. Quaker History, 101, (1), 1-11.

Marshall, E. (1973, June 9). Nixon’s way to the top. The New Republic, 15-19.

McGinnis, J. (1969). The Selling of the President 1968. Simon & Schuster.

N. A. (1977). Transcript of David Frost’s interview with Richard Nixon. Teaching American History. https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/transcript-of-david-frosts-interview-with-richard-nixon/

N. A. (2004, August 8). Report: Nixon Drunk in ’73 Crisis. CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/report-nixon-drunk-in-73-crisis/

Pierleoni, A. (2017, April 21). Author of new Nixon biography cites parallels between Tricky Dick and Trump. Sacramento Bee. Points of View Reference Center.

SNL Transcripts Tonight. (n.d.). SNL transcripts: Madeline Kahn: 05/08/76: Final Days. https://snltranscripts.jt.org/75/75snixon.phtml

Thomas, E., & Shackelford, L. (1997). Nixon off the record. Newsweek, 130 (18), 52.

Vivian, A. (2016). The cold war: Nixon and Khrushchev: The kitchen debate. In M. Shalley-Jensen (Ed.), The cold war: Nixon and Khrushchev: Defining documents in American history: The 1950s (pp. 101–105). Salem Press.

Woodward, B. & Bernstein, C. (2005). The Final Days. Simon & Schuster.